Film, media and related arts - subjective contemplation and commentary with consideration of the intrinsic duality, interminable relevance and evolution of each. Exhibition of original and contributed film, art, music and writings.

Tuesday, May 31, 2022

The Optical Files #76: Scarface - The Diary (1994)

Sunday, May 29, 2022

The Optical Files #75: Beck - Odelay (1996)

Friday, May 27, 2022

The Optical Files #74: Blackalicious - Blazing Arrow (2002)

Wednesday, May 25, 2022

The Optical Files #73: Talib Kweli - Right About Now (2005)

Monday, May 23, 2022

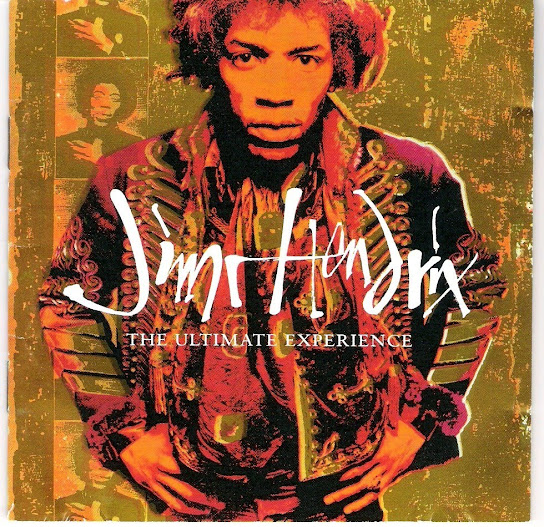

The Optical Files #72: Jimi Hendrix - The Ultimate Experience (Compilation) (1992)

Sunday, May 22, 2022

The Optical Files #71: KRS-One - The Mix Tape / Prophets vs. Profits (2002)

Friday, May 20, 2022

Bressonian Quote #29 - Notes from a Master Filmmaker

Thursday, May 19, 2022

The Optical Files #70: Bob Dylan - The Times They Are A-Changin' (1964)

When I was an adolescent, this was my favorite Bob Dylan album. I think my tastes were even grimmer back then than they are today because this is the bleakest Bob Dylan album...well, ever. After the empowering but still foreboding opening title track, there is only a single ray of sunlight, in the form of the uplifting "When the Ship Comes In." The other 8 songs are full of war ("With God On Our Side"), economic devastation ("Ballad of Hollis Brown," "North Country Blues"), racial violence ("Only A Pawn In Their Game," "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll"), & permanent goodbyes ("One Too Many Mornings," "Boots of Spanish Leather," "Restless Farewell"). Depending on how I'm feeling, the darkness of this album is almost suffocating--& whether in spite of that fact or because of it, it's still my favorite of his early acoustic period.

It's also the album that begins his transition from the strident topical songwriting of his first 2 to the more artistically free music he'd start making with the next one. Dylan is still somewhat in his imitative stage here, as this album owes a great debt to Woody Guthrie--from the oblique-angle adaptations of traditional refrains to the aw-shucks demeanor concealing his polemical intentions to the gently massaged Marxism (in a nation of such abundance, there's no reason people's literal lives should depend as much on economic factors as the protagonists of "Ballad of Hollis Brown" & "North Country Blues"). The former song is a masterpiece of sonic storytelling: by simply picking a single minor chord the entire time (a trick he's reusing from "Masters of War" on the previous album), Dylan creates a droning, insistent musical backdrop. It doesn't change when you think it should--kinda like Hollis's life--which gets creepier the longer it goes on. The latter half of the song throws a series of close-up images at the listener, like a sequence of monochrome crime scene photos: a patch of blackened grass, a handful of shotgun shells, a shotgun that moves from the wall to a farmer's hands. On top of those details & devastating imagery ("your wife's screams are stabbing you like the dirty driving rain"), Dylan shifts the mode of address from the 1st person ("his cabin broken down") to the 2nd person ("your children are so hungry that they don't know how to smile"). The shift makes an already confrontational song even more so--Dylan puts the listener in Hollis's shoes, left with the implicit question of how it all came to this.

Another song that feels visual to me is "One Too Many Mornings," which Dylan sings in a near-whisper while doing some elegant (if simple) fingerpicking. He paints a delicately-observed picture of the narrator leaving a room, & noticing the details both inside & outside. Nothing is overtly stated, but you somehow know that the lovers referenced in the song will not be lovers much longer. Another shift in the mode of address occurs here, but it is more ambiguous as to whether "my love" in the 2nd verse is the same person addressed as "you" in the 3rd, but I feel like it is. "One Too Many Mornings" says more in 120 words than most breakup songs can say in 5 times that.

"Only a Pawn In Their Game" commemorates the assassination of NAACP leader Medgar Evers, & points out the ways the racist establishment turns poor white people against black people, but rather than using that to excuse or ameliorate the crimes of racial terrorists like Evers' assassin, in Dylan's view it adds to their degradation. He points out that Medgar will be remembered as a king, but his murderer will never be anything more than a pawn.

Even this album's production is thinner than before or after: there are no full band breaks like "Corrina, Corrina" on the previous album or piano like "Black Crow Blues" on the following one. We are stuck with Dylan's trebly guitar, thin reedy voice & piercing harmonica (& there's even less of that than we've been used to). All of this adds up to a record that I can't just listen to at any time--maybe when I was younger I could, but I've seen too much of the world now to take this stuff lightly. I have to be in the mood to hear this, but when I am, there are few albums, from Dylan or anybody else, that hit quite this hard.

Tuesday, May 17, 2022

The Optical Files #69: Public Enemy - Apocalypse 91...The Enemy Strikes Black (1991)

Monday, May 16, 2022

The Northman - Featured Film of Interest

Sunday, May 15, 2022

The Optical Files #68: Ice Cube - Death Certificate (1991)

Friday, May 13, 2022

The Optical Files #67: Cold Crush Brothers - All The Way Live in '82 (1994)

Thursday, May 12, 2022

Wednesday, May 11, 2022

The Optical Files #66: KRS-One - KRS-One (1995)

Monday, May 9, 2022

The Optical Files #65: The Beatles - Magical Mystery Tour (1967)

Saturday, May 7, 2022

The Optical Files #64: The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Electric Ladyland (1968)

Thursday, May 5, 2022

The Optical Files #63: Bob Dylan - John Wesley Harding (1967)

Still recovering from a serious motorcycle accident, taking what would prove to be an 8-year break from touring, & working out lots of songs with the group that became known as The Band, when Dylan returned to the studio in 1967 it was with a very different outlook. The album that resulted from these sessions was an earthy antidote to the art-rock excesses of Blonde on Blonde, both musically & lyrically. The music on John Wesley Harding is sparse to the point of minimalism, & the strange verbal strategy plus the consistent sound add up to an album that's hypnotically soothing & almost tantric in its contemplation.

9 of the album's 12 songs are played by a trio: Dylan on guitar & harmonica, Charlie McCoy on bass & Kenny Buttrey on drums. I've always loved Buttrey's drums on this album: dryly produced, insistent, but full of subtle touches like his shift into a funk/soul pattern in the back half of the title track. McCoy is also a star here: with such a minimalist arrangement, the bass has plenty of room to shine, & his active playing livens up songs like the Irish folk-inspired "As I Went Out One Morning," which is almost a showcase for him. An album this rustic has no business being this funky too, but the rhythm section makes it so.

The guitar/bass/drums/harmonica setup is so consistent that when another instrument does pop up--like the piano in "Dear Landlord" & "Down Along the Cove," or the steel guitar in the latter song & "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight"--it's striking, as if the whole album has taken a big turn just by adding 1 instrument. "Dear Landlord" is probably the most interesting composition here, with more playful bass runs by McCoy & Buttrey laying down a heavily swinging blues shuffle. Bob plays swanky chords on the piano & sings it with more soul than we'd really heard from him up to this point. "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight" also plays with genre, unfolding as a pure country 2-step ballad with the twangy pedal steel to prove it. It simultaneously points toward the next album Nashville Skyline whilst being more country than anything thereupon.

Dylan's lyrical strategy has undergone an evolution too since the 3-album run that preceded this. No longer is he using extravagant language to obscure meaning--he's now using simple language to tell riddles. There is a mystical quality to the songs here in their simplicity & their oblique religious references. The lyrics feel more like zen koans than songs--for the first time, it seems Dylan doesn't want you to decode his lyrics, he just wants you to let the sounds & associations seep into your brain.

If you noticed I've used a lot of words in this writeup like tantric, mystical, religious, & zen, that's because in some opaque way, John Wesley Harding is a deeply spiritual album. It's not explicit in any given song, but the congregate impression is of more searching & grasping for faith than any of his explicitly Christian albums from subsequent decades.

"My trip hasn't been a pleasant one, & my time it isn't long/& I still do not know what it was that I've done wrong."

Wednesday, May 4, 2022

Relevant Film Quote: Hank - Swiss Army Man

"Well, you can't just say everything that comes into your head. That's bad talking."